14th June 2017 was almost like a 9/11 event for the fire safety industry. It is, of course, the date of the Grenfell Tower fire. For anybody employed in the fire safety industry and watching the horror unfold, it was an unforgettable event that would have far-reaching consequences.

Those employed in the passive fire safety sector were already aware that most buildings, old and new, were seriously lacking in the integrity of fire and smoke compartmentation. Trade associations had been shouting aloud on this subject since the introduction of fire safety legislation changes in 2006.

As a result, there were not as many surprises as there perhaps should have been. The surprise in this case was learning that the composite construction flat entrance doors, tested as part of the investigation by the Metropolitan Police, failed to consistently meet the 30-minute fire resistance standard.

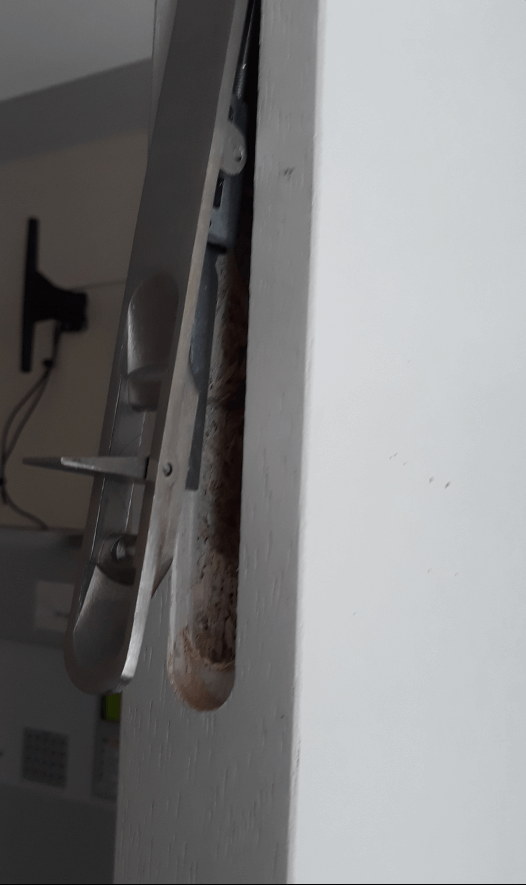

You can read more here about the advice given by MHCLG. Furthermore, many in the fire door sector were aware that the installation of fire doors was more often than not defective and fell short of the relevant standard.

What happened next after the Grenfell Tower fire?

As far as fire doors are concerned and in our experience, three significant things happened:

- MHCLG conducted tests on more composite construction fire doors and then more tests on timber-based fire doors. The tests revealed that a high percentage of composite construction fire doors failed to meet the fire resistance requirements whereas all timber-based fire doors reached or surpassed the requirements. Some manufacturers of composite fire doors withdrew from the market. Others improved their products, carried out further tests in line with requirements set out in MHCLG advice notes and returned to the market.

- Following Dame Judith Hackitt’s report, a competence steering group was set up to look at the competence of people working on high-rise residential buildings (HRRBs). This steering group recently published its interim report and the proposals, if implemented, mean it could be one of the biggest shake-ups the construction industry has seen in decades. This ‘shake-up’ would certainly affect the fire door sector.

- Fire door inspectors saw a large increase in enquiries from building operators and from construction companies. They were all anxious to ensure that the fire doors at their premises or installed by their contractors were compliant with the relevant standard and, importantly to them, that ‘a certificate’ can be provided.

So, what does this mean?

While it’s certainly welcome that greater focus is now on fire doors being compliant, it has also raised some issues. These issues have to be addressed and it is to be hoped that the competence steering group will be successful, over time, in doing much to help.

One important issue is that many building operators, and seemingly fire risk assessors, are often unable to identify which doors at their buildings are necessary as fire doors. Building operators have had a legal obligation to carry out suitable and sufficient fire risk assessments since the Fire Safety Order was implemented back in 2006. They are also required, as necessary, to appoint Competent Persons to assist them in this task. The risk assessments must be updated as and when made necessary by changes. Clearly, a fire risk assessor that cannot identify the fire doors necessary to the fire strategy cannot claim competence. Maintaining fire doors as fit for purpose can be an expensive business so it’s essential that the building operator knows which doors are necessary as fire resisting doors; in many buildings there are more sets of blue circular fire door signs than there are fire doors!

Currently, it is to be hoped that the fire door inspector, when they are engaged, makes the building operator aware of this issue. If not, then pockets will need to be deeper than should be the case!

Another main issue is that many fire door installers are not competent at installing fire doors.

When fire doors are purchased, installation instructions will be available. It is not possible to install a fire door without reference to the instructions. There is very little by way of standardisation when it comes to installing different fire doors as they each have their own requirements based on the evidence of fire performance for that particular door type. Two doors of similar size and outward appearance may have different installation requirements. These can range from intumescent seal size to the maximum lock size and hinge positions. This is because they are made by different manufacturers, or even by the same manufacturer, but have different core constructions. There is currently no legal requirement for fire door installers to have dedicated installation training but, in the case of high-rise residential buildings, this is addressed in the ‘Raising The Bar’ interim report.

Raising the bar

The intention of the working groups set up by the competence steering group is to improve the fire safety integrity of high-rise residential buildings. They plan to achieve this by setting nationally recognised requirements for levels of competence required to perform certain tasks related to the construction of these types of buildings. Those tasks would include inspection and consultancy work, as well as installation and maintenance work. This is part of a requirement for fire risk assessors, fire door inspectors and fire door installers to demonstrate that they possess the necessary competencies to carry out their work at high-rise residential buildings.

If the proposals contained in the report are implemented, those working on HRRBs will need to undergo recognised training and CPD. This is to be welcomed as it represents an improvement on the current situation where no dedicated qualifications are necessary, or where certification has been attained. It refers only to the contracting company or organisation, not the person actually carrying out the task.

There is no doubt that raising the bar in this regard will be a good thing for the future for those living in HRRBs. There is also a good argument for extending the proposals to cover buildings such as some hospitals and residential care facilities.

Unintended consequences

There is always a concern that, when making changes that are intended to become mandatory, the consequences may make certain situations worse than before; be careful what you wish for!

Clearly trying to introduce benchmark competence levels for all of the different trades and roles involved in the construction of HRRBs will be a huge task. Doing it successfully will be even more of a task.

Taking fire doors as an example and limiting the focus to HRRBs alone, will the regulatory body overseeing competence be able to ensure fire doors are installed competently across the complete sector?

Bearing in mind that it could possibly take the failure of just one fire door to cause harm to others in a fire situation, will the regulator be able to ensure that small-scale fire door replacement work, by one flat owner for example, will be in-scope? As well as what would be the case for new-build or large scale refurbishment projects?

Will all fire door installers require a CSCS card even if their normal fire door installation and maintenance work is carried out on a small scale at existing buildings rather than at construction sites?

Will existing fire door installers be disenfranchised by requirements for third-party certification?

These installers may already have the necessary competencies but it could be that they only install or maintain a small number of fire doors. They may be a small business or sole trader and the cost of attaining third-party certification may, for them, be prohibitive. Clearly, excluding such competent persons would fall under the heading of ‘unintended consequences’.

These installers may already have the necessary competencies but it could be that they only install or maintain a small number of fire doors. They may be a small business or sole trader and the cost of attaining third-party certification may, for them, be prohibitive. Clearly, excluding such competent persons would fall under the heading of ‘unintended consequences’.

There are already a limited number of fire door training options available. These include installation and inspection for example and setting a benchmark for the quality of that training is to be welcomed. However, as a consequence, it may be necessary for previously qualified fire door installers and inspectors to undertake additional training at extra cost. Such training must be easily accessible and affordable as well as of sufficient quality. Anything other than that may lead installers to move out of the fire door sector and work where additional training is not a necessity.

If accredited third-party certification for fire door installers, maintainers and inspectors becomes a mandatory requirement, there will be a definite need for the quality and depth of such certification schemes to be improved.

There are still instances where the work of a third-party certificated contractor or supplier fails to meet the relevant standard meaning that the client is short-changed in terms of the quality of the work as well as the price paid.

Also, there is still a tendency among some contractors and clients to value the certification over the quality of the work. This box-ticking attitude must not be allowed to prevail.

Certification is not always a guarantee of quality. It ought to be.